- Home

- Alleyn, Susanne

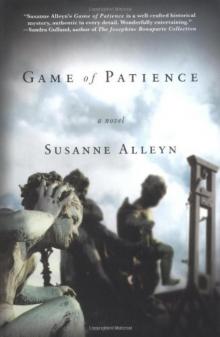

Game of Patience Page 3

Game of Patience Read online

Page 3

CHAPTER 3

Aristide turned away at last from the dead man. “Didier, have you found the murderer’s pistol?”

“No. Must have taken it with him.”

“You say Saint-Ange’s manservant discovered the bodies?”

Didier jerked his head toward a door in the salon. “He’s in the dressing room. He’d gone out on errands for his master at about four o’clock yesterday and was gone all night. When he returned, he found what you see.”

“Did no one else see or hear anything?”

“We’re inquiring now. Half the house is untenanted. The rent’s high in this quarter.”

“And there are plenty of empty mansions for the wealthy to buy cheap,” added Brasseur, “if you do have the money to live in style. Who’d want to live in a flat when you can have some duke’s fancy town house? Well, go on,” he told Didier.

“The apartment below is vacant, so no one seems to have heard the struggle or the shots.”

“But the servant’s absence, combined with Prunelle’s opinion, gives us the time it happened, within an hour or two,” Aristide said. “Unless you suspect the servant?”

Didier shrugged. “Not likely. What motive are you thinking he’d have?”

“I agree,” Aristide said, ignoring Didier’s deliberate insolence. “Unless there was something between him and the girl, but that does seem improbable.”

At a nod from Brasseur, the waiting guardsmen carried the two bodies down the stairs. Aristide knelt on the carpet, gazing about him.

“Brasseur.”

He held up a fragment of paper between his forefinger and thumb. It was a tiny triangular scrap, cream colored with a black band and narrow black stripe edging the two shorter sides, and frayed on the third edge. He rose and dropped it into Brasseur’s outstretched palm. “What do you think?”

“Looks like a piece torn off an assignat,” Brasseur said instantly. He pulled a folded banknote from his pocket, glancing from one to the other. “Look there: you can see the printing in the corner, p-u-n, where it says ‘The law punishes the counterfeiter with death.’ ”

“You said Saint-Ange had money on him, Didier? Was it in his pocket?”

Didier nodded. Aristide surveyed the effects laid out on the lacquered cabinet: pocketbook, handkerchief, the girl’s reticule, a few copper coins and prerevolutionary silver écus, a thick bundle of assignats in various denominations. “Why not try leaving things as they were, instead of insisting upon your precious inventory?” he added, shuffling rapidly through the notes. Didier glowered.

“Procedure—”

“Quite a lot here,” Aristide said, ignoring him. “Several hundred thousand livres’ worth.”

“A few louis’ worth in gold, I expect,” Brasseur grunted, “what with the value of paper money these days. I swear, the stuff’s fit only to wipe your arse.”

“Ah, here, I think.” Aristide held up a worn, crumpled five-livre note. One corner was missing and the words at the frayed edge matched the scrap of paper he had found.

“It’s only a guess, but I’d venture that this note, and probably others, changed hands recently, if a piece of it was lying on the carpet. He thrusts a handful of notes into a pocket, a frayed corner tears off and falls. When had the room last been swept?”

“The manservant will know,” said Didier. “Did you wish to question him now, Commissaire?” He went out and returned with a short, dark man of about forty-five.

“So,” Brasseur said, consulting Didier’s notes, “you are Barthélemy Thibault, domestic servant, in service with Saint-Ange for two years?” The man nodded. “And you left this house at about four o’clock yesterday to attend to some errands.”

“That’s right, Citizen Commissaire. I had to complain to the caterer who delivers his meals that the midday roast was overdone.”

“You returned this morning? Isn’t that a long time to be absent?”

“It was Sunday—I mean décadi—” He paused, reddening. “I’m sorry, citizen, I still have trouble with this republican calendar, even after three years …”

“Don’t we all?” said Brasseur, shrugging. “Go on.”

Aristide permitted himself a slight smile. The new official calendar had been created in 1793 to divorce the French Republic from such outdated, superstitious relics of the old order as the Christian reckoning and its numerous religious festivals and saints’ days. In his experience, the new months and the ten-day week drove most people to distraction; it was still necessary to include the Christian date, with a discreet “old style” beside it, on all the newspapers.

“Well,” Thibault continued, “it was décadi, like I said, and he’d given me the evening off, once I was done with the message, so I visited the cabaret for a spell, and had a few glasses with some friends. Then I ran into a girlfriend of mine, you see, and I spent the night at her lodgings. Saint-Ange never rose before nine, so as long as I got back before eight, in time to build up the fire and heat his water and brew his coffee, I was all right.”

“Well, go on.”

“I got back about seven this morning, I think, or a little after.” He rubbed his eyes and grimaced. “Seems already like a year ago. I came up the staircase and tried unlocking the door very quietly, so as not to wake him, but it wasn’t locked.”

“It looks as if Saint-Ange let the murderer in himself,” Aristide said. “The door wasn’t broken in.”

“So I went in on tiptoe,” Thibault continued, “thinking he’d just forgot to lock the door. And first thing I saw was the furniture all every which way, and then the poor young lady. I touched her cheek and she was cold. And then I went farther and saw him and I knew right away from that hole in his head that he was dead, and I ran down to send for help. Couldn’t have been longer than ten minutes about it.”

Aristide stepped forward. “Thibault, I want you to tell us your honest opinion, no matter what it may be. What did you think of Saint-Ange?”

“Well, he was always decent to me.” Thibault scratched his head. “Not a difficult man to work for, like some.”

“Do you know the source of his income?”

“Said he owned land in the country that he rented to farmers. Bought up cheap when they sold off the church property for the government. Said he’d once owned a sugar plantation in Saint-Domingue, though he lost that when the Negroes revolted.”

“Did he?” Aristide glanced about him. “This apartment is furnished more luxuriously, I’d hazard, than a man could afford whose sole income was a few rents. Last year’s inflation would have ruined him.”

“I wouldn’t know about that.”

“Kept his affairs to himself? All right then,” Aristide continued, “tell me about his friends who called on him. You claim you’ve never seen the young lady before?”

“Yes. I mean, no, I’ve never seen her before.”

“But you’ve seen other women here.”

“Oh, yes, a fair stream of them. His present lady friend was here yesterday. I know her; she’s been visiting him for weeks. They went out to the Palais-Égalité for luncheon, then came back here and spent the rest of the afternoon in his bedchamber,” he added, with a smirk. “Well, he was a young man, and good-looking, and with enough money in his pocket to have a good time; and living right by the Palais-Égalité, after all! You can’t blame him, can you?”

“To each his own taste, I suppose. Did you see this woman leave? Did they seem on good terms?”

“Yes, she left about four o’clock. There wasn’t nothing wrong between them—they couldn’t keep their hands off each other. That was a little before Citizen Saint-Ange told me to take the message to the caterer.”

“Were all his visitors courtesans?”

“He had other visitors now and then. A different sort. Some gentlemen, and other women; what they used to call—before the Revolution—‘ladies of quality.’ Well dressed; and most of them shy. They’d come wearing veils or deep hoods to their cloaks. Like they didn’t

want to be recognized.”

“Do you know what business they had with Saint-Ange?”

“No, he sent me off on errands when they called, or gave me ten sous and told me to go have a glass in the gardens. And when he gave me ten sous for a glass of red that cost two or three, I was glad enough to get it and keep my mouth shut.”

“Just one last question, Thibault. When was this salon swept last?”

“Day before yesterday,” Thibault said promptly. “A woman comes in every day to do the heavy cleaning, except for décadi. She’ll be back today, or she would be if …”

Brasseur snapped his notebook shut. “Thanks. You can go with one of the inspectors now, and give him your statement.” He turned to the window and stared out to the street as Thibault left the room.

“I tend to wonder,” he said, still gazing out the window at the silent, shuttered house opposite, “when I hear of a prosperous fellow with no particular means of income, who’s visited by all sorts of women. And who keeps a loaded pistol in his cabinet. Dangerous thing to do, that, but useful if you’re on the lookout for trouble.”

“What does it all smell like to you?” said Aristide.

“A pander, I expect. A high-class one; a flesh peddler living off loose women.”

Aristide shook his head. “Perhaps. But Thibault said many of his visitors, not just the one who died with him, were timid, respectably dressed ladies. And this girl had no money on her at all, except for a few sous which happen to be about the price of a cab fare home, wherever in Paris home is. And Didier found a sizable bundle of notes on Saint-Ange. The stink is fouler than pandering, I imagine.”

Brasseur smacked his fist into his palm.

“Extortion!”

“I think I begin to mislike the late Louis Saint-Ange. And perhaps to believe whoever murdered him did the world a service.” Aristide wheeled about, staring down once again at the spot where the dead girl had fallen. “One of his victims must have grown desperate and rid himself—or herself—of a most rapacious parasite. I wouldn’t expend too much effort in trying to learn who the killer was. But that poor girl had to die, too… .”

“She must have been one of his victims,” Brasseur said. “You thought she’d been crying… .”

“Yes. Pleading with him, perhaps. Probably she was trying to keep secret some childish indiscretion from a father or a fiancé.”

“We’ll know more when she’s identified,” said Brasseur. “A nicely-dressed young lady like that, she’s sure to have someone wondering where she is, parents or at least servants.” He turned to Didier. “Inspector, station a man here in the building, in the porter’s room. And try not to let the news of Saint-Ange’s death spread too far. Keep that porter quiet; keep him flat-out drunk if you have to. Anyone who comes to call on Saint-Ange is to be held for questioning.”

“Whom were you thinking of catching?” Aristide said.

“If we’re right about Saint-Ange, another of his victims will probably come by with a payment soon, or at least one of his friends. Didier, I’m to be sent for as soon as you bag someone.”

“Yes, Commissaire.”

“And mind you treat them properly,” Aristide added. “The Terror’s over. Innocent witnesses give information more willingly if they’re not frightened half to death.”

“I don’t take orders from you,” said Didier, coloring. “You’re not even an inspector.”

“You will if I say you do,” Brasseur snapped. “Ravel works for me and gets paid by me, same as you; he may not have an official title, but he’s an agent of the police, understood?”

“Yes, Commissaire,” Didier said, adding under his breath, “Never thought I’d be taking orders from a damned spy.”

Aristide ignored him. Spy or talebearer were the first epithets that sprang to most people’s minds when they learned he worked for the police, but not openly as an inspector, peace officer, or commissaire. Some aspects of policing had not changed since the collapse of the old regime; the vast majority of “police agents” had always been spies and eavesdroppers, loathed by all including their employers, forever ready, for a small stipend, to repeat indiscreet talk or report observations and rumors.

Aristide held the common police spy in as much contempt as did anyone else, preferring to devote himself to investigation rather than informing. The difference that preserved his self-respect, he thought, was that when he went undercover, it was to obtain evidence about crimes committed, for the sake of justice; while informers usually gathered loose talk and innuendo, hints of crime and sedition that had not yet occurred, for the benefit of suspicious authority.

He strode out to the landing, glad to be away from the room in which the faint smell of gunpowder still hung. “Which of the apartments are tenanted?” he asked Didier, over his shoulder. “Have you questioned them all?”

“The people two floors above heard some scuffling yesterday evening,” Didier muttered, “but they didn’t think anything of it. They’re too far above, and you can’t hear much in a stone house like this. The wife might have heard shots; but she admitted she got so used to shots in the street in ’ninety-two and ’ninety-three that she scarce thought anything of it, except to close the shutters and be grateful she was indoors. She’s a pretty stupid sort of female. They also think they could have heard someone running up and down the staircase. The family just above was out at the theater all evening, every damned one of them, including the servants, and they don’t know anything. Most people in the quarter were out for the day, since it was décadi and fine weather for a change.”

Aristide nodded and they continued down the stairs to the porter’s lodging by the street door. The porter sat slouched at a table, a brandy bottle beside him.

“Out in the hallway, if you please, Citizen Grangier,” Brasseur said. Eyes darting toward Brasseur’s tricolor sash, the porter shambled out to the foyer. The two men carrying the girl’s shrouded body stepped forward. With a swift movement, Brasseur jerked away the sheet.

“Know her?”

The porter recoiled and shook his head.

“Sure? Take a good look.”

“I—I don’t know who she is. I didn’t do it. I swear to God, I didn’t do it—”

“No one is suggesting you did,” Brasseur said patiently. He gestured the man back into his lodging, muttering “Well?” to Aristide as he followed Grangier inside.

“No,” said Aristide. “That’s not a man with murder on his conscience.”

“I agree.” Brasseur sat on the nearest bench and gestured Aristide and Dautry, his secretary, to stools.

“But I saw who did, citizen,” the porter said eagerly. “It must have been him that did it. I saw him on the staircase. First I heard footsteps going up the stairs. Very fast, they were. I didn’t see him then—I’d just woken from my afternoon nap—”

“Isn’t that part of your job, to watch who goes in and out, and to direct callers toward the right apartment?”

“Well, yes, but them as knows the house just come in. And if you need to know which floor somebody lives on, you can look at the names outside.”

Aristide nodded. Since 1793, the law had required the names of all tenants to be inscribed on the outside of the house by the entrance.

“So you heard someone running up the stairs,” he said. “What time was this?”

“About six o’clock. Almost time to light the lamp in the foyer. I get up, and put my head out the door in case he needs anything, but he’s gone already. So I sit myself down again and have a dram of brandy and a bit of sausage I’ve been saving for my supper, and then a bit later I hear the footsteps again, coming down fast. It’s all stone and plaster in the stairway, you know, and the sound echoes. So I put my head out again and I just catch sight of him as he races out the door to the street.”

“Did you see his face?”

“No, just his back. He had on a dark coat and top boots. And long hair.”

“Like mine?” Aristide said, push

ing his own long hair away from his face.

“Not so dark, citizen, and his was gathered back. Like I said, I didn’t get much of a glimpse of him. But when he came back—”

“He came back?” Brasseur exclaimed.

“Yes, he came back, it might have been twenty minutes, a half hour later. That time I got a better look at him. He came running in again like all the devils of Hell were behind him, and I saw his face for a moment then as he passed me. A young fellow, very pale and scared looking.”

“Scared looking?” Aristide said, glancing over at the secretary, who was furiously scribbling notes. “Are you getting all this, Dautry? Go on, Grangier; he was frightened of something?”

“Well, no, not frightened, but upset. Like I said, he was white as a sheet.”

“A young man? How old?”

Grangier nodded, eyeing the brandy bottle. “Young. Closer to a boy than a man. Twenty-five, maybe. And thin.”

“Please describe him as well as you can. His hair was dark brown, you say, but not as dark as mine? What about his eyes?”

“Didn’t see. It was getting dark, and he went by too fast.”

“How tall was he?”

“A little under medium height, I’d guess. Maybe a couple of fingers shorter than I am. He went by too fast—”

“I understand. Tell me more about his clothing.”

“Like I said, top boots and a dark coat.”

“What color? What about his culotte and waistcoat?”

The porter reached for the brandy bottle but Brasseur slid it smoothly away from him.

“This won’t improve your memory, Grangier. Try to remember.”

“Blue,” said Grangier, after a moment. “Maybe. It was getting dark in the hall. His coat was dark blue. Or it might have been dark green. His breeches were black. Didn’t see his waistcoat; he had his coat buttoned.”

“Did he wear a hat?”

Game of Patience

Game of Patience